This essays discusses Anton Chekhov’s story ‘The Lady with the Little Dog’ published in Russian in 1899 and in English three years later. The essay makes the case that this deceptively simple story (which Nabokov described as “one of the greatest stories ever written” ) illustrates the mould-breaking innovations in approach, structure, style and technique which Chekhov introduced to the short story form. It demonstrates Chekhov’s position as what one might call a late-19th Century, proto-Modernist. His short stories establish a literary bridge between Victorian-era fiction – heavily laden with deterministic plot, character detail, classically antagonistic relationships and a recurring tendency towards formal narrative closure or resolution – and a more open, ambiguous and multidimensional portrayal of the human condition within realistic settings, with recognisably realistic characters and narrative structures that resist movement inexorably towards seemingly ineluctable conclusions or resolution.And ends some two thousand or so words later. We shall see.

Oscar Wilde wrote: “Most people are other people. Their thoughts are someone else's opinions, their lives a mimicry, their passions a quotation.”

Pages

Showing posts with label literature. Show all posts

Showing posts with label literature. Show all posts

Thursday, April 07, 2016

Chekov essay in on time

It begins ...

Labels:

ANU,

literature,

reading,

short story,

study,

writing

Location:

Gilmore ACT 2905, Australia

Thursday, March 03, 2016

Rave on John Donne?

|

| Earliest known image of John Donne, around 1590 |

It's not hard to be seduced by the bravado of the early-period poems, their common tongue, their focus on sex, the irreverence of their implied commentary on the hierarchies of the poet's time. He would lose that outsider's edge as he advanced through Courtly patronage and his misogyny seems never to have been far from the surface in any period. But here we are, more than 400 years later and there is still much to be said for and learned from the inventiveness and daring of a poet who would be dead by my age.

We looked at one of his post-coital, morning after poems in today's tutorial. As Van Morrison urged, Rave On John Donne. Well ... up to a point Van, up to a point.

I wonder, by my troth, what thou and I

Did, till we loved? Were we not weaned till then?

But sucked on country pleasures, childishly?

Or snorted we in the Seven Sleepers’ den?

’Twas so; but this, all pleasures fancies be.

If ever any beauty I did see,

Which I desired, and got, ’twas but a dream of thee.

And now good-morrow to our waking souls,

Which watch not one another out of fear;

For love, all love of other sights controls,

And makes one little room an everywhere.

Let sea-discoverers to new worlds have gone,

Let maps to other, worlds on worlds have shown,

Let us possess one world, each hath one, and is one.

My face in thine eye, thine in mine appears,

And true plain hearts do in the faces rest;

Where can we find two better hemispheres,

Without sharp north, without declining west?

Whatever dies, was not mixed equally;

If our two loves be one, or, thou and I

Love so alike, that none do slacken, none can die.

Location:

Gilmore ACT 2905, Australia

Friday, February 19, 2016

Why this man writes

| Orhan Pamuk. Pic by Columbia University Press |

As you know, the question we writers are asked most often, the favourite question, is; why do you write? I write because I have an innate need to write! I write because I can't do normal work like other people. I write because I want to read books like the ones I write. I write because I am angry at all of you, angry at everyone. I write because I love sitting in a room all day writing. I write because I can only partake in real life by changing it. I write because I want others, all of us, the whole world, to know what sort of life we lived, and continue to live, in Istanbul, in Turkey. I write because I love the smell of paper, pen, and ink. I write because I believe in literature, in the art of the novel, more than I believe in anything else. I write because it is a habit, a passion. I write because I am afraid of being forgotten. I write because I like the glory and interest that writing brings. I write to be alone. Perhaps I write because I hope to understand why I am so very, very angry at all of you, so very, very angry at everyone. I write because I like to be read. I write because once I have begun a novel, an essay, a page, I want to finish it. I write because everyone expects me to write. I write because I have a childish belief in the immortality of libraries, and in the way my books sit on the shelf. I write because it is exciting to turn all of life's beauties and riches into words. I write not to tell a story, but to compose a story. I write because I wish to escape from the foreboding that there is a place I must go but – just as in a dream – I can't quite get there. I write because I have never managed to be happy. I write to be happy.The whole speech is here: My Father's Suitcase

Labels:

literature,

me,

reading,

study,

writing

Location:

Gilmore ACT 2905, Australia

Wednesday, February 17, 2016

Heroism in The Iliad

|

| Ajax carries the body of Achilles |

There's a reading group discussion underway on The Guardian web site looking at Homer's Iliad. Today's topic is considering the heroism or otherwise of Achilles. One of the contributors noted that the literal translation is 'warrior' rather than 'hero' - a modern appellation, which the Greeks of classical times would not have understood as we do today. Here's my two-bob's worth of a response to 'emilyhauserauthor's post.

"the ancient Greek word ἥρως ('heros', usually translated as hero), actually means just a 'warrior'. It doesn't have any of the additional connotations we've come to expect of moral worth, valour, and so on. In a sense, then, expecting 'heroism' of Achilles - to expect him to conform to any of our ideas of what a 'hero' is - is an anachronism."

This is a persuasive observation / reminder. The modern / romanticised notion of the hero (not just an effective warrior but just, righteous, dare one say almost invariably Christian in English Lit.) simply doesn't fit with either of Homer's works (Odysseus, it seems to me, similarly exhibits none of the attributes of the modern hero when he conspires with Telemachus to ambush the suitors).

Achilles is a demi-god warrior par excellence who has - like all the invaders around him - been away from home and family for a decade. Three thousand years before the John Wayne caricature of 'the good soldier' fighting 'a just war' stepped on to our screens. What should we expect of such men at such a time in those circumstances?

As I think someone else suggested too, anyone looking for an Homeric character coming closest to our modern idea of heroic (perhaps I mean courageous) should look to Priam - an old, broken man who at great personal risk sets out to recover his son's body so that the honour and respect due to the rites set out by Gods may be observed and Hector's eternal position secured.

Is Hector a hero? Reluctant perhaps, possessed of questionable judgement and a problematic war time leader of a doomed nation. One may feel sorrow at his fate and admit his bravery in stepping out to meet Achilles but ... I'm not sure those are either modernity's heroism or the classical warrior.

Labels:

literary criticism,

literature,

poetry,

reading

Location:

Gilmore ACT 2905, Australia

Tuesday, February 09, 2016

John Gray o' Middleholm

|

| James Hogg, 'the Ettrick Shepherd' painted by Sir John Watson Gordon |

Today I read one of his short stories, included in Philip Hensher's Penguin anthology. 'John Gray o' Middleholm' was published around 1820 or 1821 in a collection by Hogg which was titled, Winter Evening Tales, Collected Among the Cottagers in the South of Scotland. It must have been a popular enough two-volume collection because the version "Digitized by Google" is an 1821 Second Edition printed by Oliver & Boyd in Edinburgh.

Nearly two hundred years old, describing a lost Scotland and people whose lot has fallen into history mostly - home-based weavers, cobblers, the remnants of an agricultural peasantry 'John Gray' has more common - in an odd sense - with characters out of Mark Twain or Rip Van Winkle than with urban Scots or those from the Victorian-era onwards.

It made me laugh in places, this moderately hokey tale of a Borders' ne'er-do-well, always short of money, always hungry with a long-suffering, gossiping and not very bright wife, too many children and daft ideas of the ways he'll rise above his lowly station. Is it a ghost-tale? Not really although there is definitely an uncanny twist. Is it a homily to thrift and the rewards of hard work? Not at all, although a prodigious annual harvest of fruit might make you think so at first. Anyway, it's an enjoyable, gentle satire. Well worth reading, it has earned its place in Mr. Hensher's review of 250 years of British short story telling.

Labels:

fiction,

literature,

reading,

short story,

study,

writing

Location:

Gilmore ACT 2905, Australia

Tuesday, January 26, 2016

Burns Night on Australia Day

| Robert Burns - 1759 to 1796 |

January 25th is the celebration of the birth and life of Scotland's national poet, Robert Burns. He was born on the 25th January in 1759 in the village of Alloway, south of the town of Ayr. Here in Australia today it's our national holiday commemorating - increasingly controversially - the arrival of the 'First Fleet' in the great southern land in 1788. The vast continent would be claimed as territory for King George III by Captain Arthur Phillip when he and a dozen or so oarsmen and military personnel landed at Sydney Cove from HMS Supply. The other ships in the fleet were marooned in Botany Bay by a fierce storm. Burns was 29 years old on that very day.

My blog draws its name from Burns who wrote a poem To A Louse: On Seeing One On A Lady's Bonnet, At Church (1786). I'm the louse that answered back.

My friend Stuart Hepburn (we met at university where we were political rivals in fiercely opposed left-wing camps) delivered an astonishing, awe-inspiring rendition of Burns's comic masterpiece Tam O'Shanter, written in 1790. I believe you'll not come across a finer interpretation of the poem anywhere than Stuart's rendition. Burns would be the first to raise a glass and cheer.

Labels:

australia,

literature,

me,

poetry,

Robert Burns,

Scotland

Location:

Gilmore ACT 2905, Australia

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

So good it does your head in

A gift to myself arrived from England a few days ago. Today I got round to reading Andrew McMillan's first collection of poems, physical, which won the Guardian First Book Award 2015. It's not difficult to see why it was a contender.

I read the short collection in one sitting; read it aloud because poetry like this benefits from being read out loud. The absence of punctuation wasn't a hindrance. The rhythm of the poems takes you through the text. Almost without conscious thought you learn quite quickly, perhaps intuitively, that two spaces between words signifies a comma, three tells you where a full stop might be. And the lines seem to fit with the simple but profound idea that where you need to take a pause for breath the text requires a break as well.

There are echoes (for me at least) of Marianne Moore in the tightly structured verse (I thought of The Steeplejack and Poetry when I read protest of the physical, a magnificent longer poem). I heard the whisper of T S Eliot in WHEN LOUD THE STORM AND FURIOUS IS THE GALE. There is even a bit of Billy Collins in THE FACT WE ALMOST KILLED A BADGER IS INCIDENTAL. Best of all though, this a collection from a unique and confident voice. A true poet.

I read the short collection in one sitting; read it aloud because poetry like this benefits from being read out loud. The absence of punctuation wasn't a hindrance. The rhythm of the poems takes you through the text. Almost without conscious thought you learn quite quickly, perhaps intuitively, that two spaces between words signifies a comma, three tells you where a full stop might be. And the lines seem to fit with the simple but profound idea that where you need to take a pause for breath the text requires a break as well.

There are echoes (for me at least) of Marianne Moore in the tightly structured verse (I thought of The Steeplejack and Poetry when I read protest of the physical, a magnificent longer poem). I heard the whisper of T S Eliot in WHEN LOUD THE STORM AND FURIOUS IS THE GALE. There is even a bit of Billy Collins in THE FACT WE ALMOST KILLED A BADGER IS INCIDENTAL. Best of all though, this a collection from a unique and confident voice. A true poet.

Labels:

literature,

poetry,

reading

Location:

Gilmore ACT 2905, Australia

Friday, January 08, 2016

No single fact can ever define us - two strong women

Another two short stories from Philip Hensher's anthology bit the dust today; both by women whose long lives straddled the turn of 18th and 19th Centuries, both of whom experienced mental breakdown, both of whom survived their traumas to write.

Hannah Moore was born in 1745, the year of the Jacobite Rebellion. She wrote plays, poems and short stories such as the morality tale, Betty Bridges, the St. Giles's Orange Girl. It's too easy to observe that such a one-dimensional tale of the moral improvement made possible through hard work, thrift, respect for God's laws and the beneficent power of the philanthropic middle-classes could not be written today. But it's just as true that Miss More wrote her short, unmistakably 'Dickensian' fable three years before the great chronicler of London's poor was born. Hannah was a leader of the Bluestocking group (maybe not proto-feminist but certainly supportive of educated, intellectual, socially-conscious and engaged women). And when it came to the great cause of her day - the abolition of the slave trade - Hannah More was on the right side of history.

Mary Lamb was born twenty years after Hannah More and lived to the middle of the 19th Century. What sorts of changes must these two women have seen in their lives, each of more than eight decades? It was an era of enormous change in the structure, economy, society of Great Britain - the great age of the industrial revolution that made Victorian Britain the largest Empire the world had ever known. Where Hannah More's story centred on the misfortunes of the urban poor and the reforming efficacy of the emergent middle-class, Mary Lamb's nostalgic rumination on childhood, The Farm House, harked back, I think, to fabrications of a lost (perhaps never-existed) agrarian idyll. I was startled, then, to discover that aged 32 Mary Lamb stabbed to death her mother who was sitting at their dinner table. Mary was convicted of lunacy, spending short periods in institutions throughout the rest of her life. She and her brother Charles were, however, fully engaged members of London's literary life.

|

| Hannah More by Henry Pickersgill |

|

| Mary Lamb |

Labels:

fiction,

literature,

reading,

short story

Location:

Gilmore ACT 2905, Australia

Saturday, January 02, 2016

Prometheus was not wrong

I'm going to start an online course next week, studying Shelley's Prometheus Unbound. Before I do I thought I better acquaint myself with the great Romantic poet's inspirational source. So, today, I read a version of Prometheus Bound taken from The Harvard Classics series with a translation by someone called Edward Haynes Plumptre (1821 - 1891).

We know the Titan was not wrong in what he foresaw. Io accepted his vision of her future because he could recount her past correctly. He knew where she had come from and could tell where she was going. Prometheus could foresee the line of births that would lead from Io to Heracles and back, the circle completed, to the release of Prometheus from his chains.

So we know Prometheus was not wrong to reject the deal offered by Hermes. Recant and Zeus would set him free ... more accurately, release him from the shackles. Continue to resist and Zeus would heap a "triple wave of ills" upon his head: buried alive in a ravine for an immeasurable age; exposed thereafter to the light so that the eagle of Zeus could feed each day on Prometheus's liver; finally cast into the dungeon Tartarus, lower even than the depth of Hades.

And Prometheus replied:

To me who knew it all

He hath this message borne;

And that a foe from foes

Should suffer is not strange.

Therefore on me be hurled

The sharp-edged wreath of fire;

And let heaven’s vault be stirred

With thunder and the blasts

Of fiercest winds; and earth

From its foundations strong,

E’en to its deepest roots,

Let storm-wind make to rock;

And let the ocean wave,

With wild and foaming surge,

Be heaped up to the paths

Where move the stars of heaven;

And to dark Tartaros

Let Him my carcase hurl,

With mighty blasts of force:

Yet me He shall not slay.

|

| Heracles freeing Prometheus from his torment by the eagle |

So we know Prometheus was not wrong to reject the deal offered by Hermes. Recant and Zeus would set him free ... more accurately, release him from the shackles. Continue to resist and Zeus would heap a "triple wave of ills" upon his head: buried alive in a ravine for an immeasurable age; exposed thereafter to the light so that the eagle of Zeus could feed each day on Prometheus's liver; finally cast into the dungeon Tartarus, lower even than the depth of Hades.

And Prometheus replied:

To me who knew it all

He hath this message borne;

And that a foe from foes

Should suffer is not strange.

Therefore on me be hurled

The sharp-edged wreath of fire;

And let heaven’s vault be stirred

With thunder and the blasts

Of fiercest winds; and earth

From its foundations strong,

E’en to its deepest roots,

Let storm-wind make to rock;

And let the ocean wave,

With wild and foaming surge,

Be heaped up to the paths

Where move the stars of heaven;

And to dark Tartaros

Let Him my carcase hurl,

With mighty blasts of force:

Yet me He shall not slay.

Labels:

drama,

fiction,

literature,

study

Location:

Gilmore ACT 2905, Australia

Friday, January 01, 2016

More short stories - back in the 18th Century

I read a couple of tales from Philip Hensher's anthology, both from the middle of the 18th Century. Neither will make it into my list of all-time greats. I'm not entirely persuaded they merit a place in a review of the British short story across 300 years of literary history. Mr. Hensher concedes some of my reservations when he writes that,

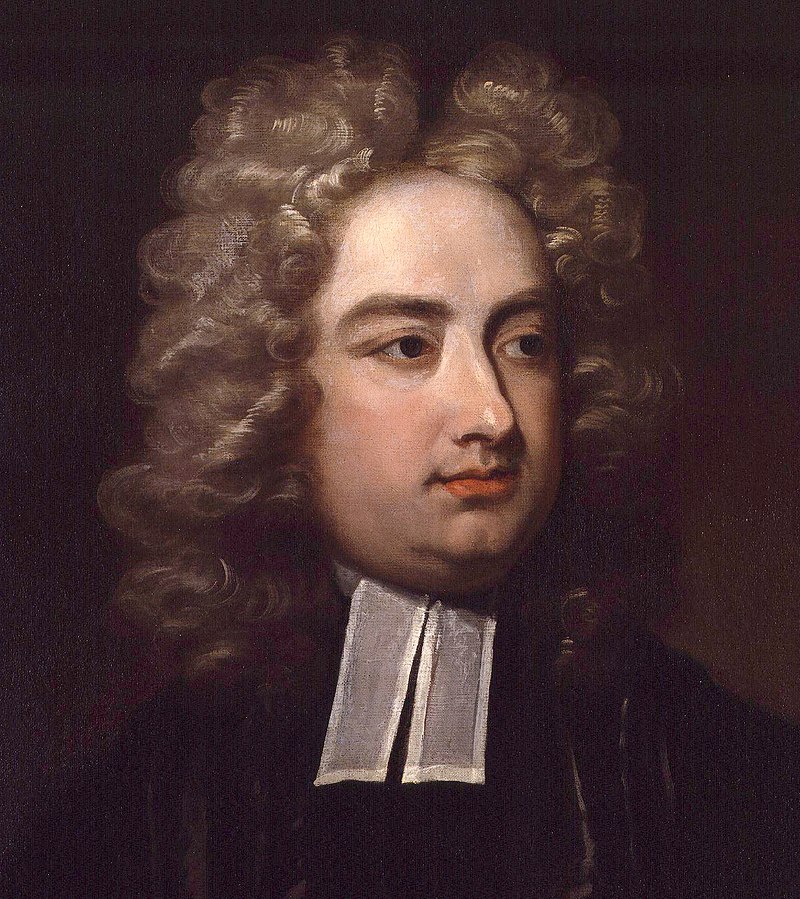

I'm not a fan of Jonathan Swift. For reasons that surprise me I struggle a bit with satirical writing generally and with Swift in particular. I'm not entirely sure why that is; something to do, perhaps, with the way it ages so very quickly. That and what I think of as a fine line between satire on the one hand and cynicism, condescension and even misanthropy on the other. Jonathan Swift, I've long felt, tends towards all three of the latter.

Gulliver's Travels has always struck me as a distasteful book and it's not a surprise that most attention has been given to the first two adventures (often in a form rendered safe for children). By the time you encounter the Yahoos I think we're in thoroughly unsavoury territory, even for its time.

Reading Directions to the Footman didn't do anything to rehabilitate Swift in my mind. Its condescending, nasty tone was never going to appeal to me. He may be mocking some of the absurdities of the British class system in 18th Century England but he does so by laughing at the servant classes first and foremost. Make up your own mind: you can read it here.

Henry Fielding's story The Female Husband seems to me to have all kinds of story-telling problems; too many, I feel, to be contained within the twenty or so pages the tale takes. Maybe Fielding could get away with it in his longer fiction. I don't know because I've never read any of it. Is that a shocking admission for a man with my pretensions to make? Probably. Now I suppose I shall have to read Tom Jones. As unlikely a tale as The Female Husband may be, it turns out its origins lay in historical fact, which wiki sets out here. Shows me how wrong I can be.

"The first pieces in this anthology are not, in the modern sense, short stories But they bear in a vital, animating way on the short story's historical development. They are trying to distinguish themselves from the long form, and are drawing on a number of literary counter examples."And I think ... maybe. But Philip Hensher read many, many more short stories in preparing his anthology than I shall ever read (I suspect) so I'll take him at his word; accept his judgement. That still doesn't make me any more enamoured of the second and third stories in his first volume, by Jonathan Swift and Henry Fielding.

|

| Jonathan Swift, by Charles Jervas |

Gulliver's Travels has always struck me as a distasteful book and it's not a surprise that most attention has been given to the first two adventures (often in a form rendered safe for children). By the time you encounter the Yahoos I think we're in thoroughly unsavoury territory, even for its time.

Reading Directions to the Footman didn't do anything to rehabilitate Swift in my mind. Its condescending, nasty tone was never going to appeal to me. He may be mocking some of the absurdities of the British class system in 18th Century England but he does so by laughing at the servant classes first and foremost. Make up your own mind: you can read it here.

|

| Henry Fielding, etching by Jonathan Wild |

Labels:

fiction,

literature,

reading,

short story

Location:

Gilmore ACT 2905, Australia

Tuesday, July 31, 2012

Imagining America

My university study proper resumed today with the first

classes of my literature unit (Imagining America, led by Dr David Kelly with

whom I’ve studied previously – his Literature and Cinema course on book to film

adaptations). Typically (for me) I

mossed the first class, a one hour lecture, thanks to a meeting running over at

work. I suppose I can’t complain too

much. NDS is allowing me the flexibility

I need to study at all. But I’ll try

hard in the future not to miss classes.

I did make it to the first of our weekly two-hour seminars; this week an

introduction to the course as a whole. I

volunteered to take the first week’s seminar topic (next Tuesday) on Walt Whitman

with a particular focus on The Song of

Myself. I was the only person to put

my hand up for Whitman, which I was rather pleased about. I’m not keen on undergraduate group

work. To be honest, it’s because every

time it’s foisted upon me my mark drops a notch or two.

This afternoon we discussed the idea of America ,

considered within the context of American Exceptionalism and ‘the American

experiment’ in nationhood and nation-building.

There were divergent views on the extent to which the exceptionalism

notion still features in contemporary political philosophy (as distinct from

current political discourse). I tended

towards that remains live within both philosophy and discourse (thinking of

Bush and the Neo-Cons not so long ago or the Tea Party today). A couple of my fellow students argued a

similar perspective (with a sounder base in fact than I offered). Dr Kelly saw it as less real in the current

political philosophies at play in modern America

although still a strong driver in the public discourse of candidates competing

for office. He argued (I think) that we’re

in a different phase, beyond the triumphant and imperialist march of the great

20th Century powerhouse, although the USA remains a great power but

the hegemony of the white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant elite that emerged from the ‘founding

fathers’ is waning (Dr Kelly suggests) as the nation fragments, diversifies and

re-considers internally its foundation myths while, economically and

culturally, the idea of American hegemony in a globalised economy as reached

its limits.

|

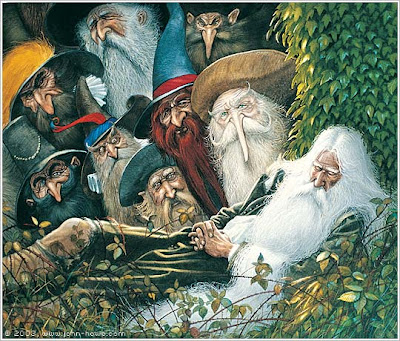

| Rip Van Winkle by John Howe |

We started our literary examination of an imagined America

with Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle. I read the story as a child. The only part that stuck with me was the part

about the man who falls asleep for 20 years.

I remember it as a modern fairy tale – Dr Kelly used the term ‘tall tale’

which has more meaning in the American context; that’s the tradition Faulkner

was invoking with As I Lay Dying. Although

I read the story before the class and was able to offer some analysis and

interpretation of it – particularly around the portrayal of women, the soft

spot it exhibits for the laconic, ne’er do well male hero, the reassurance of continuity

and progress around or across the bifurcating disruption of the long sleep,

among others - I was struck by the differences between Dr K’s much closer, more

analytical reading of the text than I could manage. I realise, of course, that he’s a full time

academic at a major institution and that American literature is one of his

areas of interest. Nevertheless, I

should have been able to see more than I did.

My reading must become more analytical.

I need to become more rigorous in asking myself what’s going on and

seeing the answers present in the text.

So I didn’t adequately describe the contrast in women’s roles before and

after the big sleep (Dame Van Winkle may be a shrew but she has agency; Rip Van

Winkle’s daughter is domesticated and nurtures the next male generation). I didn’t see the satire on the monarchy or on

the transfer of power from King George to George Washington (asking the

question, to what extent has circumstances truly changed / improved for

ordinary people?).

The point is this: I must sharpen my powers of

observation. I need to see better what

it is that’s going on inside a text, not simply what’s happening with or to the

story or its characters. I’m looking

forward to the rest of the semester. I may

even learn something.

Labels:

fiction,

literature,

reading,

Sydney University

Monday, July 09, 2012

The Murders of the Rue Morgue

|

| Charles Gemora plays the ape in the 1932 film |

It seems so quaintly old-fashioned despite its graphic, Gothic imagery of violence. When it was published though, it must have been read as shockingly modern. Did Poe invent the private detective with his character Dupin? He pre-dates Sherlock Holmes by nearly fifty years and must surely have been part of Conan Doyle's thinking as he constructed the acutely perceptive, supremely analytical Holmes.

Labels:

fiction,

literature,

reading,

Sydney University

Sunday, July 08, 2012

Reading Walt Whitman

I have said that the soul is not more than the body,

And I have said that the body is not more than the soul,

And nothing, not God, is greater to one than one's self is,

And whoever walks a furlong without sympathy walks to his own funeral drest in his shroud,

And I or you pocketless of a dime may purchase the pick of the earth,

And to glance with an eye or show a bean in its pod confounds the learning of all times,

And there is no trade or employment but the young man following it may become a hero,

And there is no object so soft but it makes a hub for the wheel'd universe,

And I say to any man or woman, Let your soul stand cool and composed before a million universes.

(Song of Myself, the opening lines of Section 48)

And I have said that the body is not more than the soul,

And nothing, not God, is greater to one than one's self is,

And whoever walks a furlong without sympathy walks to his own funeral drest in his shroud,

And I or you pocketless of a dime may purchase the pick of the earth,

And to glance with an eye or show a bean in its pod confounds the learning of all times,

And there is no trade or employment but the young man following it may become a hero,

And there is no object so soft but it makes a hub for the wheel'd universe,

And I say to any man or woman, Let your soul stand cool and composed before a million universes.

(Song of Myself, the opening lines of Section 48)

Labels:

literature,

poetry,

reading,

Sydney University

Sunday, June 24, 2012

Midnight's Children

Not having been to bed overnight, I'm very tired. But I managed a couple of (short) chapters from Book 2 of Salman Rushdie's Midnight's Children. It truly is a masterpiece of 20th Century literature; written beautifully, in places lyrical but still demonstrably modern; hugely imaginative, bursting with references to the modern age (not simply post-colonial Indian history) and overflowing with ideas. All that and it's funny too. Everyone should read it.

In the early evening I read some of Poe's verse (and criticism thereof). There was The Raven (of course) and a couple of his earlier works, To The River (1829) and The Sleeper (1830). I can't quite decide if I think The Raven is a bold, great poetic work or really not very good at all. Yeats inclined to the latter view I believe and he's a hard man to ignore.

The Raven

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore,

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

`'Tis some visitor,' I muttered, `tapping at my chamber door -

Only this, and nothing more.'

Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December,

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow; - vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow - sorrow for the lost Lenore -

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels named Lenore -

Nameless here for evermore.

And the silken sad uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me - filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating

`'Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door -

Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door; -

This it is, and nothing more,'

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer,

`Sir,' said I, `or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore;

But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping,

And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door,

That I scarce was sure I heard you' - here I opened wide the door; -

Darkness there, and nothing more.

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before;

But the silence was unbroken, and the darkness gave no token,

And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, `Lenore!'

This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, `Lenore!'

Merely this and nothing more.

Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning,

Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before.

`Surely,' said I, `surely that is something at my window lattice;

Let me see then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore -

Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore; -

'Tis the wind and nothing more!'

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter,

In there stepped a stately raven of the saintly days of yore.

Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he;

But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door -

Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door -

Perched, and sat, and nothing more.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

`Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,' I said, `art sure no craven.

Ghastly grim and ancient raven wandering from the nightly shore -

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night's Plutonian shore!'

Quoth the raven, `Nevermore.'

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly,

Though its answer little meaning - little relevancy bore;

For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being

Ever yet was blessed with seeing bird above his chamber door -

Bird or beast above the sculptured bust above his chamber door,

With such name as `Nevermore.'

But the raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only,

That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour.

Nothing further then he uttered - not a feather then he fluttered -

Till I scarcely more than muttered `Other friends have flown before -

On the morrow he will leave me, as my hopes have flown before.'

Then the bird said, `Nevermore.'

Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken,

`Doubtless,' said I, `what it utters is its only stock and store,

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore -

Till the dirges of his hope that melancholy burden bore

Of "Never-nevermore."'

But the raven still beguiling all my sad soul into smiling,

Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird and bust and door;

Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking

Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore -

What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore

Meant in croaking `Nevermore.'

This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing

To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom's core;

This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining

On the cushion's velvet lining that the lamp-light gloated o'er,

But whose velvet violet lining with the lamp-light gloating o'er,

She shall press, ah, nevermore!

Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by Seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor.

`Wretch,' I cried, `thy God hath lent thee - by these angels he has sent thee

Respite - respite and nepenthe from thy memories of Lenore!

Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenthe, and forget this lost Lenore!'

Quoth the raven, `Nevermore.'

`Prophet!' said I, `thing of evil! - prophet still, if bird or devil! -

Whether tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted -

On this home by horror haunted - tell me truly, I implore -

Is there - is there balm in Gilead? - tell me - tell me, I implore!'

Quoth the raven, `Nevermore.'

`Prophet!' said I, `thing of evil! - prophet still, if bird or devil!

By that Heaven that bends above us - by that God we both adore -

Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn,

It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels named Lenore -

Clasp a rare and radiant maiden, whom the angels named Lenore?'

Quoth the raven, `Nevermore.'

`Be that word our sign of parting, bird or fiend!' I shrieked upstarting -

`Get thee back into the tempest and the Night's Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken! - quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!'

Quoth the raven, `Nevermore.'

And the raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon's that is dreaming,

And the lamp-light o'er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted - nevermore!

In the early evening I read some of Poe's verse (and criticism thereof). There was The Raven (of course) and a couple of his earlier works, To The River (1829) and The Sleeper (1830). I can't quite decide if I think The Raven is a bold, great poetic work or really not very good at all. Yeats inclined to the latter view I believe and he's a hard man to ignore.

The Raven

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore,

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

`'Tis some visitor,' I muttered, `tapping at my chamber door -

Only this, and nothing more.'

Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December,

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow; - vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow - sorrow for the lost Lenore -

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels named Lenore -

Nameless here for evermore.

And the silken sad uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me - filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating

`'Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door -

Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door; -

This it is, and nothing more,'

Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer,

`Sir,' said I, `or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore;

But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping,

And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door,

That I scarce was sure I heard you' - here I opened wide the door; -

Darkness there, and nothing more.

Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before;

But the silence was unbroken, and the darkness gave no token,

And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, `Lenore!'

This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, `Lenore!'

Merely this and nothing more.

Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning,

Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before.

`Surely,' said I, `surely that is something at my window lattice;

Let me see then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore -

Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore; -

'Tis the wind and nothing more!'

Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter,

In there stepped a stately raven of the saintly days of yore.

Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he;

But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door -

Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door -

Perched, and sat, and nothing more.

Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

`Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,' I said, `art sure no craven.

Ghastly grim and ancient raven wandering from the nightly shore -

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night's Plutonian shore!'

Quoth the raven, `Nevermore.'

Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly,

Though its answer little meaning - little relevancy bore;

For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being

Ever yet was blessed with seeing bird above his chamber door -

Bird or beast above the sculptured bust above his chamber door,

With such name as `Nevermore.'

But the raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only,

That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour.

Nothing further then he uttered - not a feather then he fluttered -

Till I scarcely more than muttered `Other friends have flown before -

On the morrow he will leave me, as my hopes have flown before.'

Then the bird said, `Nevermore.'

Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken,

`Doubtless,' said I, `what it utters is its only stock and store,

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore -

Till the dirges of his hope that melancholy burden bore

Of "Never-nevermore."'

But the raven still beguiling all my sad soul into smiling,

Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird and bust and door;

Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking

Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore -

What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore

Meant in croaking `Nevermore.'

This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing

To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom's core;

This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining

On the cushion's velvet lining that the lamp-light gloated o'er,

But whose velvet violet lining with the lamp-light gloating o'er,

She shall press, ah, nevermore!

Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by Seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor.

`Wretch,' I cried, `thy God hath lent thee - by these angels he has sent thee

Respite - respite and nepenthe from thy memories of Lenore!

Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenthe, and forget this lost Lenore!'

Quoth the raven, `Nevermore.'

`Prophet!' said I, `thing of evil! - prophet still, if bird or devil! -

Whether tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted -

On this home by horror haunted - tell me truly, I implore -

Is there - is there balm in Gilead? - tell me - tell me, I implore!'

Quoth the raven, `Nevermore.'

`Prophet!' said I, `thing of evil! - prophet still, if bird or devil!

By that Heaven that bends above us - by that God we both adore -

Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn,

It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels named Lenore -

Clasp a rare and radiant maiden, whom the angels named Lenore?'

Quoth the raven, `Nevermore.'

`Be that word our sign of parting, bird or fiend!' I shrieked upstarting -

`Get thee back into the tempest and the Night's Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken! - quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!'

Quoth the raven, `Nevermore.'

And the raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon's that is dreaming,

And the lamp-light o'er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted - nevermore!

Labels:

fiction,

literature,

reading,

Sydney University

Monday, May 07, 2012

Very few degrees of separation

|

| Wallace Stevens |

Wallace Stevens wrote a poem called The Death of a Soldier, which I may have confused in my memory with a poem by Randall Jarrell. I remember still the shock of reading the final line of The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner.

From my mother's sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze.

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.

Labels:

literature,

poetry,

reading

Sunday, May 06, 2012

Jacob's Room

I finished Virgina Woolf's first experimental work today (it was VW's opinion that her first two novels are conventional). She tried to build a fictional world with none of the structure of the novel up to that point. So there's no beginning, middle or end (the penultimate sentence is an unanswered question). Time is pervasive but never chronological. Architecture informs character, mood, perception but we seldom linger anywhere, in any building, for long (the Reading Room of the British Museum maybe; the Parthenon and St Paul's Cathedral perhaps but always in an elliptical manner, coming back and forth, moving in and out). It's a short, affecting read. I made what may have been a mistake by playing Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata from the point in Chapter Three that Woolf writes "... the Moonlight Sonata answered by a waltz." (page 54 in my edition, Oxford World Classics). What a powerful (depressingly so) sense of a doomed, lost generation of young men it evoked. It's as effective ... not quite maybe ... as the middle section of To the Lighthouse which may be unsurpasable IMHO.

Jacob's Room is an impressive read; eye-opening about what can be done with fiction; moving. It's not perfect though (what is?). The butterfly metaphor was overdone (particularly in the chapters before we get to London) and that social strata upon which VW turns her perceptive gaze was irritatingly narrow but given who she was and how the First World War affected her own connections I suppose one can forgive her. It's certainly a novel to read but not on any day you're a bit depressed by life's ability to subdue one's enthusiasm.

Labels:

fiction,

literature,

reading,

Sydney University,

writing

Monday, April 16, 2012

You mean ... out loud?

|

| William Makepeace Thackery |

Interloper that I was, taking the class because I'll be in Perth on Friday when my usual tutorial is scheduled, I felt that one of the regulars might want to fill the gap. But no, it appeared not. Unfortunately I was unable to assist. Pretending to myself that I'm a modern reader I'd equipped myself with a Kindle version of the text on my ASUS Transformer. As the gods of anti-modernity would have it though my Tablet had died earlier in the day. That's an overstatement because Spike resuscitated the computer when I got home. So, unable to bear the painful silence I apologised for being without text, recounted briefly the sad tale of my defunct tablet and was on the point of asking the bored young women next to me if I could borrow her pristine, possibly unread, copy. Another young woman then interjected. She would read. I'm not quite sure if her threshold for pain at the awkwardness of our collective reluctance was close to mine or, perhaps, she felt sorry for the nice old man at the other side of the room who had suffered a not uncommon IT problem. Either way, she read. Between us ... her, the tutor and me ... we got a conversation going but it was hard.

I admit to puzzlement. We're students of English, aren't we? Who among us ... language barriers aside ... would not want to read out loud in the presence of such bright thinkers? I'm NOT taking the piss. It seems I'm a bit odd in this regard. I'll try not to let that stop me.

Sunday, April 15, 2012

There's Vanity Fair ...

... and there's the movie from 2004 starring Reece Witherspoon. Each is enjoyable in its own way but the latter is a pretty distant cousin of the former. But there are worse ways to spend a Sunday afternoon when you're not going far from home; not going anywhere come to think of it.

Labels:

fiction,

literature,

movies,

reading,

Sydney University

Thursday, April 05, 2012

Just write

William Wordsworth was 28 and Samuel Taylor Coleridge 26 when Lyrical Ballads, with a few other Poems was published in 1798. It may be true that it is never too late to try but I'm already older than their years combined.

Ice on Ben Arthur, 1971

Bring back the way we might have been

with our half-remembered brightness

like those eager men the world had not yet seen

restless in pursuit, not of their greatness

but of truths that they or we or any mountaineer

might look for in the glint of winter's sun

skating on the frosted summit's skin

above us; out of reach and yet so near

we dare not cease until the climb is done.

Ice on Ben Arthur, 1971

Bring back the way we might have been

with our half-remembered brightness

like those eager men the world had not yet seen

restless in pursuit, not of their greatness

but of truths that they or we or any mountaineer

might look for in the glint of winter's sun

skating on the frosted summit's skin

above us; out of reach and yet so near

we dare not cease until the climb is done.

Labels:

literature,

louse poem,

poetry,

reading,

writing

Tuesday, January 03, 2012

The Bees by Carol Ann Duffy

Wonderful read. Inspiring work. There are some excellent and very good poems here (Bees, Politics, Poetry, The Female Husband, Virgil's Bees and Rings among them). There are three poems I particularly like: Last Post, Mrs Schofield's GCSE and Atlas.

Last Post is a geat poem. It is a genuinely worthy companion piece to Wilfred Owen's Dulce et decorem est pro patria mori, perhaps the greatest (certainly best known) poem of the First World War, from which Carol Ann Duffy quotes in her poem, commissioned by the BBC to mark the deaths of the last British soldiers who had fought in the 1914 - 1918 war. Last Post will be read for generations to come. It and Ms Schofield's GCSE will be reproduced in many antholgies in the years ahead.

The bee metaphor may be a little overworked in places and unnecessary in others but that's a minor quibble. The Bees is an accomplished collection, well worth reading; well worth buying.

Last Post is a geat poem. It is a genuinely worthy companion piece to Wilfred Owen's Dulce et decorem est pro patria mori, perhaps the greatest (certainly best known) poem of the First World War, from which Carol Ann Duffy quotes in her poem, commissioned by the BBC to mark the deaths of the last British soldiers who had fought in the 1914 - 1918 war. Last Post will be read for generations to come. It and Ms Schofield's GCSE will be reproduced in many antholgies in the years ahead.

The bee metaphor may be a little overworked in places and unnecessary in others but that's a minor quibble. The Bees is an accomplished collection, well worth reading; well worth buying.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)